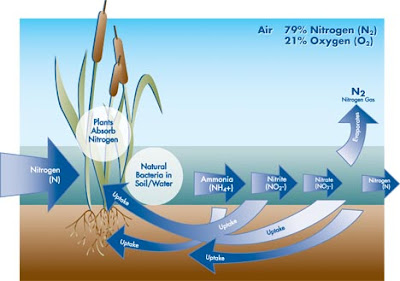

Beaver dams also play a role in slowing water run-off during periods of flooding and can help sustain flows during periods of low water. Beaver inhabited landscapes have been linked to counteracting pollution from human activities. The open nature of beaver generated environments commonly results in a vigorous community of vascular plants. Where agricultural nitrates leak into these environments they are rapidly absorbed. It has been estimated from studies in Bavaria that up to 28kg of soluble nitrates can be captured through the annual habitat creation activity of a single beaver.

Scotland

In 2009, wild beavers were first reintroduced into Knapdale Forest in Argyll, Scotland after being extinct in the UK for over 400 years. The trial is a partnership project between the Scottish Wildlife Trust, The Royal Zoological Society of Scotland and the Forestry Commission. It is the first official project of its kind in Britain and was followed by a five year study to explore how beavers enhance and restore natural environments.

|

| Breeding beavers in Scotland. Photo: RZS Scotland. |

A colony of wild beavers were spotted living on the River Otter, Devon, in February 2014. The origin of the population is unknown, It is presumed to be the result of an escape or unsanctioned deliberate release. There is now evidence of beaver activity on the River Otter from Honiton to Budleigh Salterton, a distance of around 12 miles. A breeding pair with young was filmed in 2014 on land south of Ottery St Mary. It is estimated that there are at least nine beavers on the river, including one confirmed breeding group.

|

| Beaver in the Devon trial area. Photo: David Plummer. |

In January 2015, Natural England granted Devon Wildlife Trust a licence that allowed the beavers to remain on the river, as part of a pilot experiment and five year monitoring. The River Otter Beaver Trial will work with international experts to record and evaluate the impact of the animals. At the conclusion of the project in 2020 the River Otter Beaver Trial will present Natural England with its evidence. Using this information a decision will be made on the future of the beavers on the river.

What's happening now?

Following the scientific work undertaken on the Scottish Beaver Trial, Scottish Natural Heritage have since released their report ‘Beavers in Scotland’. The report uses 20 years of work on beavers in Scotland, as well as experience from elsewhere in Europe and North America. It provides a summary of existing knowledge and offers four future beaver scenarios for Scottish Ministers to consider. The Trial is now in a holding period whilst awaiting the decision from the Scottish Government about the future for the beavers, but there is no news as of yet.

The beaver trial in England is ongoing and the surveying and monitoring is set to conclude in 2020, ready for the government to evaluate the evidence and come to a decision on the beavers remaining at the site in Devon, as well as potentially increasing trials to other locations.

It will be very interesting to see what they decide. The trials have been successful and the benefits of having beavers living naturally is proven. As well as this, the UK has obligations under the EU’s Habitats Directive to consider reintroductions of extinct native species, so reintroducing beavers to certain areas could also assist with this.

For more information and to keep up to date with the beaver trials you can visit:

http://www.ScottishBeavers.org.uk

http://www.DevonWildlifeTrust.org/devons-wild-beavers

http://BeaversInEngland.com